While nestled in my seat at the multiplex for Skyfall, the latest from the 50 year-old James Bond franchise, I thought back about how late I was to the Bond party. He was not a part of my growing up (I came from a family of girls), nor was he a character I discovered through books (preferring Le Carré or Raymond Chandler to Ian Fleming).

It wasn’t until I had a son that I came to appreciate James Bond.

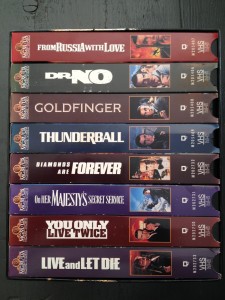

In fact, I only bellied up to the Bond bar by accident – when I bid on and won a box set of the early Bond films at a school auction. Truthfully, I bought them as a gift for a friend but somehow the present never got wrapped and one night I got wrapped up in an early title myself. It was From Russia with Love, which was released in 1963 and starred Sean Connery in the second Bond title. With a score by John Barry and incredible scenes of Russia and Istanbul, not to mention a crazy finale on the Orient Express, I was hooked. Where had I been all these years?!

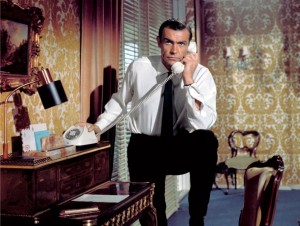

I started watching all the early films, and soon my son was watching them with me — Dr. No, Goldfinger and Diamonds are Forever — what was it about these movies that kept us riveted? No one has ever been as cool as Sean Connery, that’s obvious. But, I realized pretty quickly that it was about the guns. Of course, it began with the excellent toys that Q would give Bond — something that the latest title, Skyfall, returns to with gleeful panache. But, beyond the novelty and tricks of the weapon itself, I was struck by the clarity of how the gun was introduced into the drama of a scene, as if a character itself. Once introduced, a single gun initiated the tension that the subsequent scene had to resolve. For cineastes, this was Drama 101, but it’s easy to see how the power of a single element has gotten lost in contemporary films (and especially in video games) which glorify and highlight the spectacle of firepower.

If you have a son, the gun thing is tough. You can keep them from toy guns for only so long, but you can’t pretend forever that they aren’t part of the culture. I had done pretty well but suddenly his friends were playing with a version of BB guns, and he was begging for video games that I considered offensive. The truth is, there is a certain moment in parenting when you just can’t halt the tide of popular culture.

But you can talk about it.

We talked about about how current films often introduced thousands of weapons and bullets in a typical scene. But, in the Bond films, a single gun changed things. We talked about how James used a weapon and how justice was meted out. Even as compared to a PG-13 film like Pirates of the Caribbean, a single gun in Dr. No created more tension. (And, don’t even get me started about the bullet-fests in films such as Mr. and Mrs. Smith). A good director understands how to employ good dramatic tension, but all too often a thousand guns are used to to minimal effect. And, in Skyfall, director Sam Mendes returns to the old formula. A single bullet makes a difference in the opening scene, setting up most of the drama that ensues. James’s special issue gun saves his life in Macau and after a firefight of a finale (Oh, well…), it’s not even a gun that gets the bad guy.

I’m hardly claiming Bond as a moralistic character, but as you introduce your kids to movies, why not go back to some of the classic Bond films and start up a conversation about how movies work on our psyches? Talk about how a proliferation of killing devices can desensitize the viewer to the actual violence portrayed. As Daniel Craig has taken over the franchise (saving it, IMHO), there is a humility and darkness to his portrayal of the spy, a nod to the reality of his profession. As we celebrate all that is wonderful about the Bond franchise after 50 years, it’s encouraging to see Sam Mendes returning to the simple dramatic formulas of the early films — “sometimes the old ways are the best” as Daniel Craig mutters several times in Skyfall — but adding a layer of moral awareness that makes today’s Bond a model for coolness in 2012.