When cameras are everywhere, why paint? For David Hockney, a master of space, atmosphere and light, that’s like asking, why live?

The question drove him away from his adopted city of Los Angeles, back to his childhood home in Yorkshire, England. This was in the wake of close friends who died and his mother who passed away at 99. The journey delivered the most productive period of his career, the evidence of which is the nearly 400 works across a plethora of media in The Bigger Exhibit at San Francisco’s M. H. de Young Memorial Museum through January 20, 2014. The exhibit, from one of the world’s most renowned living artists, is exhilarating, overwhelming and sublime.

The question drove him away from his adopted city of Los Angeles, back to his childhood home in Yorkshire, England. This was in the wake of close friends who died and his mother who passed away at 99. The journey delivered the most productive period of his career, the evidence of which is the nearly 400 works across a plethora of media in The Bigger Exhibit at San Francisco’s M. H. de Young Memorial Museum through January 20, 2014. The exhibit, from one of the world’s most renowned living artists, is exhilarating, overwhelming and sublime.

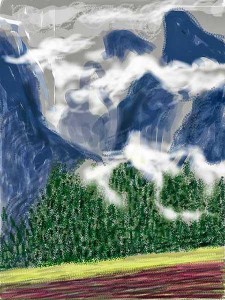

The bulk of the art is in a linked series of downstairs galleries, the descent to which recalls Alice’s fall down the rabbit hole. At the bottom we’re immersed in Hockney’s world as he moves through traditional and innovative formats including nearly 80 luminous iPad drawings of Yosemite rotated on large screens, some showing the sequence of marks applied, and an interesting video installation of a Yorkshire road during each of the four seasons.

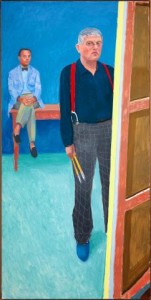

The first gallery greets us with lifesize oil portraits of his closest friends and family. Ann and David sit at a table, Richard Schmidt, Arthur Lambert and Charlie Sheips occupy their own canvases. Backdrops are medium blue or grayish white, the tiled floor is jade bounced with light. These hues set off skin tones; Hockney is the colorists’ colorist. The artist himself appears in a self-portrait in which Charlie sits on a red table in the background, dressed in a pale violet blazer, olive slacks and loafers. A marine blue wall backs the room. In the front Hockney stands gazing at us, or presumably at an unseen mirror. He sports charcoal plaid slacks, suspenders in orange, and an indigo shirt. A few paintbrushes are held at the ready in his right hand to his side while he works at the easel with his left. What’s on the canvas we assume is this picture — but we can’t see it, a tease.

We proceed on to room after room, our eyes commanding our legs. The characteristically Matisse-like palette, the summary brush strokes, rendered details, classic compositions and seamless integration of cubist elements deliver intense satisfaction.

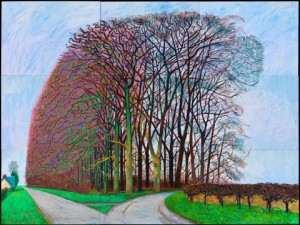

The heart of the show is the series, Spring in Woldgate, Yorkshire, 2011 to 2013. The collection includes a suite of twelve iPad compostions, each formed from four drawings, blown up, printed, mounted, simply dated, and include: 29 January, 25 March, and then 4, 11, 16, 30, 31 May, and 2 June. Nature is busy turning spring into summer during May. Nondescript roadside vistas, woods and paths that might otherwise cross our awareness without notice, in Hockney’s hand pulse with vitality, rustle with wind, and morph from dormant overgrowth into lush hedgerows. Pinks and teals oppose greens, yellows lift reds, lavenders heighten browns, and golds and whites gleam. Hockney returns over and over to the same sites, painting them at different times of day, at different seasons of the year: refrains. They’ve been called timescapes. Hockney said he feels the infinite is in the now.

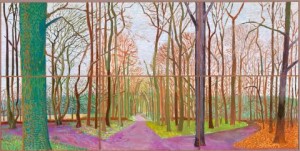

The culmination of creativity, craft and historical research comes together in a majestic room where grand painted images of Yorkshire, Yosemite and Hockney’s rendition of Claude Lorraine’s Sermon on the Mount all conspire to draw our gaze upward. The scale of these pieces is magnificent with awesome climax of Spring in Woldgate displayed as a single work in thirty-two linked canvases covering 12 feet by 30 feet, and justification for its own show alone. Shadows play throughout the woods at different times of day, somehow presented at once in a way that seems real. This is because we actually see with our memories, Hockney says, an objective view is a subset of what’s in our minds. Carpets of wildflowers and newborn leaves suspended above embrace a red path at the center strewn with sprouting grasses. As our eye travels into the painting, the trees approach us and we feel surrounded, a part of the world. The streak of golden yellow beyond the trees is an open field pulling us in further. Our vision heightens. This is what being alive is for.

The culmination of creativity, craft and historical research comes together in a majestic room where grand painted images of Yorkshire, Yosemite and Hockney’s rendition of Claude Lorraine’s Sermon on the Mount all conspire to draw our gaze upward. The scale of these pieces is magnificent with awesome climax of Spring in Woldgate displayed as a single work in thirty-two linked canvases covering 12 feet by 30 feet, and justification for its own show alone. Shadows play throughout the woods at different times of day, somehow presented at once in a way that seems real. This is because we actually see with our memories, Hockney says, an objective view is a subset of what’s in our minds. Carpets of wildflowers and newborn leaves suspended above embrace a red path at the center strewn with sprouting grasses. As our eye travels into the painting, the trees approach us and we feel surrounded, a part of the world. The streak of golden yellow beyond the trees is an open field pulling us in further. Our vision heightens. This is what being alive is for.

Since Hockney’s show at the Tate, so many people have driven to Yorkshire that a two mile stretch of road has been nicknamed Hockney Highway. The thirty mile region Hockney thought of as his wonderful garden is called Hockney National Park. A Bigger Exhibit is on display until January 20.

Review by Edie Parker